Preventing the Use of Nuclear Weapons as a Step toward a Peaceful World

The SGI Global Perspectives Committee issued the following statement on January 15, 2025.

Preamble

Between 1983 and 2022, Soka Gakkai International (SGI) President Daisaku Ikeda issued annual peace proposals addressing major world issues such as disarmament, the environment, human rights, the role of women and the United Nations. These peace proposals were issued on January 26 every year, marking the anniversary of the establishment of the SGI in 1975.

Following President Ikeda’s passing in 2023, the SGI has resolved to carry forward the efforts initiated by our mentor by periodically issuing statements on key issues as a means of raising awareness and building global consensus for action.

To this end, an SGI Global Perspectives Committee, including SGI leaders engaged in peace activities throughout the world—the Asia-Pacific region, Europe, Africa, North America and Latin America—has been created, and statements will be released from time to time outlining possible avenues to resolve the many problems facing the global community.

The first of these statements, titled “Preventing the Use of Nuclear Weapons as a Step toward a Peaceful World,” focuses on proposals for a pledge of No First Use of nuclear weapons and the establishment of a nuclear war prevention center, both of which were put forward by SGI President Ikeda in his peace proposals. It is issued in advance of the fiftieth anniversary of the SGI’s founding.

Statement

This year the world will mark eighty years since the end of World War II. Today, the protracted crisis in Ukraine has dramatically raised tensions surrounding the possible use of nuclear weapons, and the use of armed force in the Middle East, including in Gaza, continues unabated. Civilian death and suffering are escalating as humanitarian conditions worsen.

While strongly calling for the immediate cessation of hostilities, we further urge the international community to strengthen diplomatic efforts to achieve this and for all countries to cooperate in providing humanitarian assistance and support for rebuilding communities and people’s lives. In addition to these and other conflicts, global challenges such as the climate crisis, poverty and environmental destruction are intensifying, casting a bleak shadow over our future.

Nevertheless, we should not allow ourselves to be overwhelmed by pessimism. In his final peace proposal in January 2022, SGI President Daisaku Ikeda powerfully declared that people inherently possess the ability to dispel the seemingly impenetrable gloom that hangs over the world and to light the way to a hopeful future. We, members of the SGI community, share this spirit and conviction.

People inherently possess the ability to dispel the seemingly impenetrable gloom that hangs over the world and to light the way to a hopeful future.

This year marks the fiftieth anniversary of the founding of the Soka Gakkai International on January 26, 1975, on the island of Guam. Starting in 1983, the year the SGI was registered as a nongovernmental organization (NGO) with the United Nations Economic and Social Council, President Ikeda published a total of forty annual peace proposals in commemoration of January 26. As we embark on the next fifty years, the SGI will continue to issue statements on issues of planetary importance, carrying on the challenge initiated by our mentor through his peace proposals to forge an era of respect for the dignity of life. On this occasion, we would like to address the issue of nuclear weapons, a central theme running through the peace proposals authored by President Ikeda.

This year, which marks the eightieth anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, will see the holding of the Third Meeting of States Parties to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) in March and the third session of the Preparatory Committee for the 2026 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) in April and May at UN Headquarters in New York. These two meetings provide a critical opportunity to deepen deliberation on the threat of use of nuclear weapons and their inhumane nature.

The risk that nuclear weapons might actually be used is today higher than at any time since the end of the Cold War, and in this regard we would like to make two concrete proposals that must be realized with urgency. The first is to urge states to pledge never to be the first to use nuclear weapons (No First Use). The second calls for the establishment of a center dedicated to the prevention of nuclear war.

Nuclear No First Use Pledges

The TPNW, which we strongly support, unequivocally states that completely eliminating nuclear weapons is the only way to guarantee that they are never used again under any circumstances. Starting from this premise, we call on the five states signatory to the NPT as nuclear-weapon states—the United States, Russia, the United Kingdom, France and China—to initiate dialogue aimed at achieving agreement on pledges of No First Use as a first step in placing explicit limits on nuclear weapons as weapons that must never be used.

As President Ikeda stated in his proposal to the Second Special Session on Disarmament (SSOD-II) of the UN General Assembly held in June 1982, the year before he began publishing annual peace proposals:

“The situation is now critical. If we do not address the potential outbreak of nuclear war, the survival of humanity will be under grave threat. . . While it is imperative that, from the perspective that nuclear weapons are an absolute evil, we work toward the far-reaching goal of nuclear abolition, it would only require one person to press the nuclear button to end everything long before abolition can be achieved.”

This was a time reminiscent of the present situation: The world had been deeply shaken by heightened apprehension that nuclear weapons might be used, with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in December 1979 having led to a rekindling of tensions in the Cold War, and with US President Ronald Reagan hinting in October 1981 at the possibility of limited nuclear war in Europe.

Senji Yamaguchi, cochair of Nihon Hidankyo (the Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations), addressed SSOD-II as the first A-bomb survivor to speak at the United Nations. He made the powerful plea: “No more Hiroshima, no more Nagasaki, no more war, no more hibakusha!”

In the spirit of Yamaguchi’s cry, the hibakusha of Hiroshima and Nagasaki have continued to tell the world about the reality of the consequences of atomic bombing. Thanks in part to these efforts, together with those of global hibakusha affected by nuclear testing and development and of numerous civil society groups, not only was the TPNW adopted in July 2017 but to this day any further use of nuclear weapons in war has been averted. Regrettably, however, the risk that nuclear weapons will be used remains. In fact, there are serious concerns that they are being repositioned as “usable weapons,” as seen in the consideration seemingly given to their use in ongoing conflicts over recent years.

No more Hiroshima, no more Nagasaki, no more war, no more hibakusha!

Nihon Hidankyo, an organization committed to giving firsthand testimony of the actual impact of atomic bombings, received the Nobel Peace Prize in December 2024. This is evidence of the high esteem in which the international community holds Nihon Hidankyo for what its members have accomplished through decades of unstinting effort. At the same time, it conveys strong concern regarding the escalating threat of nuclear weapons use.

Sharing the resolution of the hibakusha that no one else on Earth ever suffer the horrors wrought by nuclear weapons, the SGI has published a collection of A-bomb survivors’ experiences and video testimonies from Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and has consistently called for the prohibition and abolition of nuclear weapons as engaged participants in civil society.

The starting point for these activities was the declaration calling for the abolition of nuclear weapons issued in September 1957 by Josei Toda, the second president of the Soka Gakkai. At a time when the intensifying nuclear arms race had led to the development of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), making nuclear attack anywhere on the planet possible, President Toda insisted that nuclear weapons, which threaten the right of the world’s people to live, are an absolute evil and robustly refuted the idea that they are a necessary evil that can be used depending on circumstances.

Based on this declaration, we have been striving to raise public awareness through activities such as holding exhibitions calling for the prohibition of nuclear weapons and demonstrating their inhumane nature and the threat they pose. These activities have been carried out as part of our deepening collaboration with numerous civil society organizations including the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs and International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War (IPPNW).

Following a proposal by President Ikeda on empowering the United Nations released in 2006, the SGI launched the People’s Decade for Nuclear Abolition, an international grassroots campaign, in 2007 and worked toward the objective of realizing a treaty outlawing nuclear weapons in cooperation with the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN). After the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) was adopted in 2017, we launched a second People’s Decade for Nuclear Abolition in 2018 as a civil society effort to grow international support for the treaty and universalize its principles.

The meetings of states parties to the TPNW and the NPT scheduled for the first half of this year must revive the “nuclear taboo”—the shared understanding that nuclear weapons are weapons that must never be used—which developed within international society over the decades after 1945. These gatherings must be the site of constructive deliberations on measures to prevent the use of nuclear weapons by once more bringing into sharp focus their inhumane nature. We urge the NPT Preparatory Committee in particular to further discussion of No First Use pledges, actively exchanging views on the challenges that need to be overcome and requisite institutional assurances.

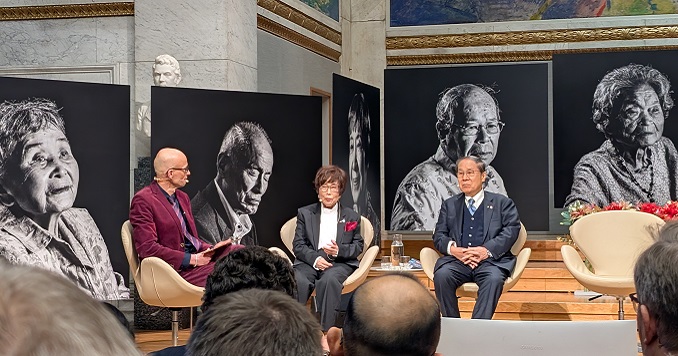

The Toda Peace Institute that President Ikeda founded in 1996 has been working to catalyze deliberation on this topic. In 2023, the SGI held a side event titled “No First Use as a Path to Nuclear Disarmament” at the first session of the Preparatory Committee for the 2026 NPT Review Conference. And in December 2024, during Nobel Week, the University of Oslo, Peacebook and the SGI co-organized a high level panel on No First Use at the University of Oslo.

Unfortunately, there is still strong hesitancy about pledges of No First Use, not only among the nuclear-weapon states but also among the nuclear-dependent states living under the “umbrella” of a nuclear-armed ally. This is because it is not easy to dispel the concern that even if one abides by the pledge oneself, another state may suddenly renege. Indeed, it may never be possible to fully resolve doubt and uncertainty regarding the actions of other nations. Nonetheless, it must be stressed that, compared to current conditions, such pledges would significantly reduce the levels of anxiety being experienced.

Half a year prior to the adoption of the TPNW, in his peace proposal of January 2017, President Ikeda introduced an insight from the teachings of Buddhism to interrogate nuclear deterrence theory:

“I would like to quote the following words of Shakyamuni, attributed to him when he was mediating a conflict between two tribes over water rights. ‘Look at those who fight, ready to kill! Fear arises from taking up arms and preparing to strike.’ It is noteworthy how Shakyamuni observes the workings of the hearts of those facing a hostile confrontation: They did not take up arms in fear of the opponent, but rather were filled with fear the moment they took up arms. While they might have felt rage toward an adversary that was trying to take their water, they were not possessed by fear. But the moment they were armed, prepared to strike deadly blows against their adversaries, their hearts were filled with dread.”

The times we live in may be different, but the human mind has surely not changed that much. Considering the challenge of changing nuclear weapon policies through the prism of Shakyamuni’s insight, it becomes clear that even if it is not possible to eliminate these deadly weapons immediately, if countries stop confronting others with weapons in hand as it were, ready for use at all times, they can start to break free from the current state of constant, mutual threat.

Even if it proves difficult to immediately agree upon an enduring commitment to the principle of No First Use, states could surely begin by agreeing to a one-year moratorium. If that first step could be taken, and if that pledge could be renewed year by year, the justifications put forward for continuing an endless nuclear arms race would gradually lose their potency. This would open a path for a reduction in the threat to which these weapons expose not only the nuclear-weapon and nuclear-dependent states but all of humankind.

A Nuclear War Prevention Center

Our second proposal is the establishment of an international center dedicated to the prevention of nuclear war.

The pledge to adhere to the principle of No First Use would inevitably require the nuclear-weapon and nuclear-dependent states to fundamentally reconsider their national security policies. Given this, it will be crucial to develop systems and measures to alleviate the fears and concerns of these countries. As one such possible measure, we would like to highlight the idea of a nuclear war prevention center—something President Ikeda proposed in his first peace proposal in 1983, along with calls for an end to the nuclear arms race and for the prompt holding of a summit between the leaders of the United States and the Soviet Union. He described specific roles of such a center as follows:

“The center could be staffed by top-level military, political and economic experts, and would collect and analyze a wide range of information through state-of-the-art computers and satellite communication networks, quickly identifying critical situations and taking steps to de-escalate.”

Such a mechanism to prevent any use of nuclear weapons is exactly what the world we live in needs. There is a historical precedent: an effort to establish such a center by the United States and Russia. In 1998, President Bill Clinton and President Boris Yeltsin agreed to share information related to the launch of ballistic missiles. This formed the basis for a memorandum of agreement signed by President Clinton and President Vladimir Putin in the year 2000, which led to the initiation of the first joint project involving military experts of the two countries.

The project was later suspended due to changes in the political environment, but the original plan called for experts from both countries to be stationed twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week at a center to be established in Moscow, with the aim of sharing information from their respective missile launch warning systems.

The basis for this project was the experience of stationing military experts from both countries at a temporary center set up in Colorado to address concerns that computer malfunctions—the so-called Year 2000 problem (Y2K)—could extend to the military realm and result in accidental missile launches. Officials from both countries offered positive appraisals of the experience, which demonstrates the real-world importance of experts from nuclear-weapon states sharing the same space and communicating in person as a means of reducing the risk of nuclear war.

From that perspective, the aim of a nuclear war prevention center would not only be to forestall missile launches caused by false information. Through regular face-to-face communication, it would also serve as a platform for fostering mutual trust between the countries involved and deepen the shared understanding that nuclear war in any form must be averted.

Three years ago, in January 2022, the leaders of the United States, Russia, the United Kingdom, France and China issued a joint statement clarifying that “none of our nuclear weapons are targeted at each other or at any other State.” Based on the spirit underlying this joint statement, we call on the nuclear-weapon states to initiate discussion on establishing such a center to prevent nuclear war.

Even if it proves difficult for all five states to act on this at the same time, as a first step, those states with an especially strong appreciation of the need for measures to prevent unanticipated outcomes could come together to implement some of its functions. As for the location of this center, one possibility would be to establish it in a key state party to one of the five Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zones (NWFZ)—Latin America and the Caribbean, the South Pacific, Southeast Asia, Africa and Central Asia—with support from the United Nations.

For the nuclear-weapon and nuclear-dependent states, commitment to No First Use pledges and the establishment of a nuclear war prevention center would require a significant reconsideration of national security frameworks. The non-nuclear-weapon states, for their part, could well consider these milestones still too distant from the ultimate goal of nuclear abolition. Nevertheless, in light of ongoing global conflicts and persistent tensions, taking such steps is urgently required if we are to avoid putting our future at even greater risk. And doing so would in fact constitute significant progress toward building a global society of peace and humane values.

On September 8, 2009, the anniversary of President Toda’s declaration calling for the abolition of nuclear weapons, President Ikeda issued a proposal specifically focused on the challenges of nuclear disarmament. The following call to action made at the end of this proposal expresses the SGI’s unwavering resolve and commitment to tackling the issue of nuclear weapons, which epitomize the evils of modern civilization:

“Based on the proud determination to make the struggle for nuclear abolition the foundation for a world without war, and convinced that participation in this unprecedented undertaking is the greatest gift we can offer the future, I call on people of goodwill everywhere to work together toward the realization of a world finally free from the menace of nuclear weapons.”

Embracing this spirit, and centered on youth—the protagonists of the future—we will continue to promote dialogue and cooperation with people from diverse cultural and religious backgrounds. We commit ourselves to the work of building a grand network of solidarity, ordinary citizens dedicated to realizing the “greatest gift we can offer the future”—a world free from the scourge of nuclear weapons.